Long John Baldry

Long John Baldry, legendry British Blues pioneer.

Long John Baldry, legendry British Blues pioneer.Just Who Was Long John Baldry?

Long John Baldry is one of those names that floats around the edges of British music history, familiar but not always fully understood. Many people know him, if at all, as the deep‑voiced singer behind the 1967 pop hit “Let the Heartaches Begin.” Yet that single, as successful as it was, barely scratches the surface of his influence. To understand the rise of British blues, and the early careers of Rod Stewart and Elton John, you must walk through the long shadow cast by Long John Baldry.

Born John William Baldry in 1941 in London, he grew up during and just after the war, discovering American jazz and blues through radio and imported records. By the late 1950s he was haunting Soho’s coffee bars and jazz clubs, absorbing the sounds of Lead Belly, Big Bill Broonzy and Muddy Waters. At well over six feet tall, he quickly earned the nickname “Long John,” but it was his booming baritone voice and encyclopaedic knowledge of blues that made him stand out on the burgeoning scene.

Before the British blues boom had stars, it had obsessives, and Baldry was one of them. He wasn’t just singing the songs; he was curating them, introducing young British audiences to artists they’d never heard of and to a style that felt raw, dangerous and utterly new. At venues like the Marquee Club and Eel Pie Island, Long John Baldry became a kind of cultural transmitter, taking American blues and handing it to British kids who would soon remake popular music.

His first serious foothold came with Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated in the early 1960s. Blues Incorporated was less a conventional band and more a revolving door of talent—a workshop where British blues was invented in real time. Baldry’s muscular vocals fronted this experiment, anchoring Korner’s passion for authentic blues. Around them, a who’s‑who of future legends passed through: Charlie Watts, (Rolling Stones), Jack Bruce, and many others. In that cauldron, Baldry refined his craft and, perhaps more importantly, began spotting and nurturing younger players.

That talent‑spotting instinct was no accident. Long John Baldry was not threatened by younger musicians; he was energized by them. He had a rare combination of deep musical knowledge, a powerful voice, and a teacher’s temperament. He could hear raw potential in a nervous kid at the back of a smoky club, then pull them forward, give them a song, a harmony part, a solo—and the confidence to believe they belonged on a stage. Over and over, he turned potential into professionalism.

Long John Introduces a Gravel Voiced Singer......

Long John Baldry's discovery, one of quite a few, Rod Stewart.

Long John Baldry's discovery, one of quite a few, Rod Stewart.One of his most famous finds was a young, shy singer with a raspy voice busking at Twickenham railway station: Rod Stewart. Baldry heard something unmistakable in Stewart’s delivery and invited him to join his band, initially the Hoochie Kooche Men. This was more than a job offer; it was an education. In Baldry’s band, Stewart learned stagecraft, repertoire, how to work a crowd, and how to embody the swaggering front‑man role that would later define his career.

The Hoochie Kooche Men, formed in the early 1960s, were Baldry’s attempt to create a hard‑driving British blues outfit that captured the intensity of his heroes. With Stewart on occasional vocals and Baldry as the main front man, they pushed electric blues into louder, tougher territory. Long John Baldry gave the group direction and discipline. He taught timing, dynamics and respect for the material—lessons that would echo through Stewart’s later work with the Faces and his solo career.

Recognise the guy with the glasses? Yes, the famous Reg Dwight, better known now as Elton John.

Recognise the guy with the glasses? Yes, the famous Reg Dwight, better known now as Elton John......Also a Promising Keyboard Player

Baldry’s influence didn’t stop with Stewart. Another uncertain young musician crossed his path: a piano player and backing singer called Reg Dwight. In the mid‑1960s, Dwight joined Baldry’s group Bluesology (sometimes misspelled as “Bliesology”) as a sideman. Sitting behind the piano, he watched how Baldry commanded a room, how he connected with audiences, and how he guided a band through very different musical moods, from earthy blues to slicker soul‑inflected pop.

The relationship between Baldry and Reg Dwight changed music history in a very literal way. When Dwight sought a stage name for his own career, he took “Elton” from saxophonist Elton Dean and “John” from Long John Baldry, creating “Elton John.” That choice wasn’t just a nod to friendship; it was an acknowledgment that Baldry had been a formative figure in his development. Elton John has spoken openly about Baldry’s personal and professional support, crediting him with helping shape both his musical direction and his life decisions.

Bluesology, the band, became one of the most polished rhythm‑and‑blues units on the British circuit. Under Baldry’s leadership, they backed visiting American artists and played residencies that required tight arrangements and versatility. Baldry’s standards were rigorous. He insisted on professionalism—punctuality, rehearsal, focus on the song rather than ego. For a young musician like Elton John, this discipline was an informal conservatory in how to be a working professional, not just a dreamer with a piano.

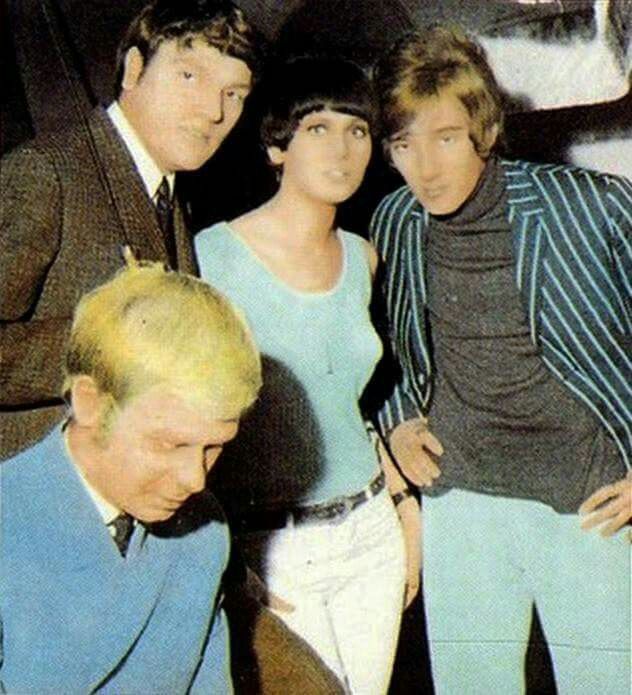

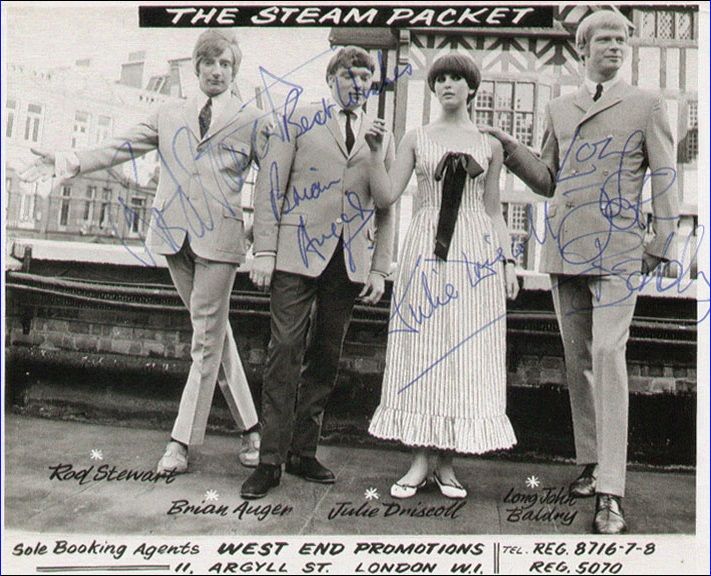

As the 1960s moved forward, British music itself was shapeshifting. The blues boom collided with R&B, soul and pop, producing ever more adventurous hybrids. Long John Baldry, always adaptable, moved with it. After the Hoochie Kooche Men, he fronted SteamPacket, an exciting but short‑lived revue‑style band that included himself, Rod Stewart, Julie Driscoll and organist Brian Auger. SteamPacket wasn’t a typical band; it was an explosive live experience, blending soul, jazz and blues with multiple lead singers and extended improvisations.

Another Steampacket line up. Rod Stewart joined by Julie Driscoll and Brian Auger.

Another Steampacket line up. Rod Stewart joined by Julie Driscoll and Brian Auger.SteamPacket never made a proper studio album, but their live shows left a deep imprint on the scene. Baldry’s role was part star, part mentor. With several vocalists to juggle, he showed how to share the spotlight while keeping the show coherent. Younger performers watched him handle transitions, pacing and audience engagement. Even without a chart legacy, SteamPacket became a key laboratory for the performance styles that would dominate late‑60s British rock and soul‑inflected pop.

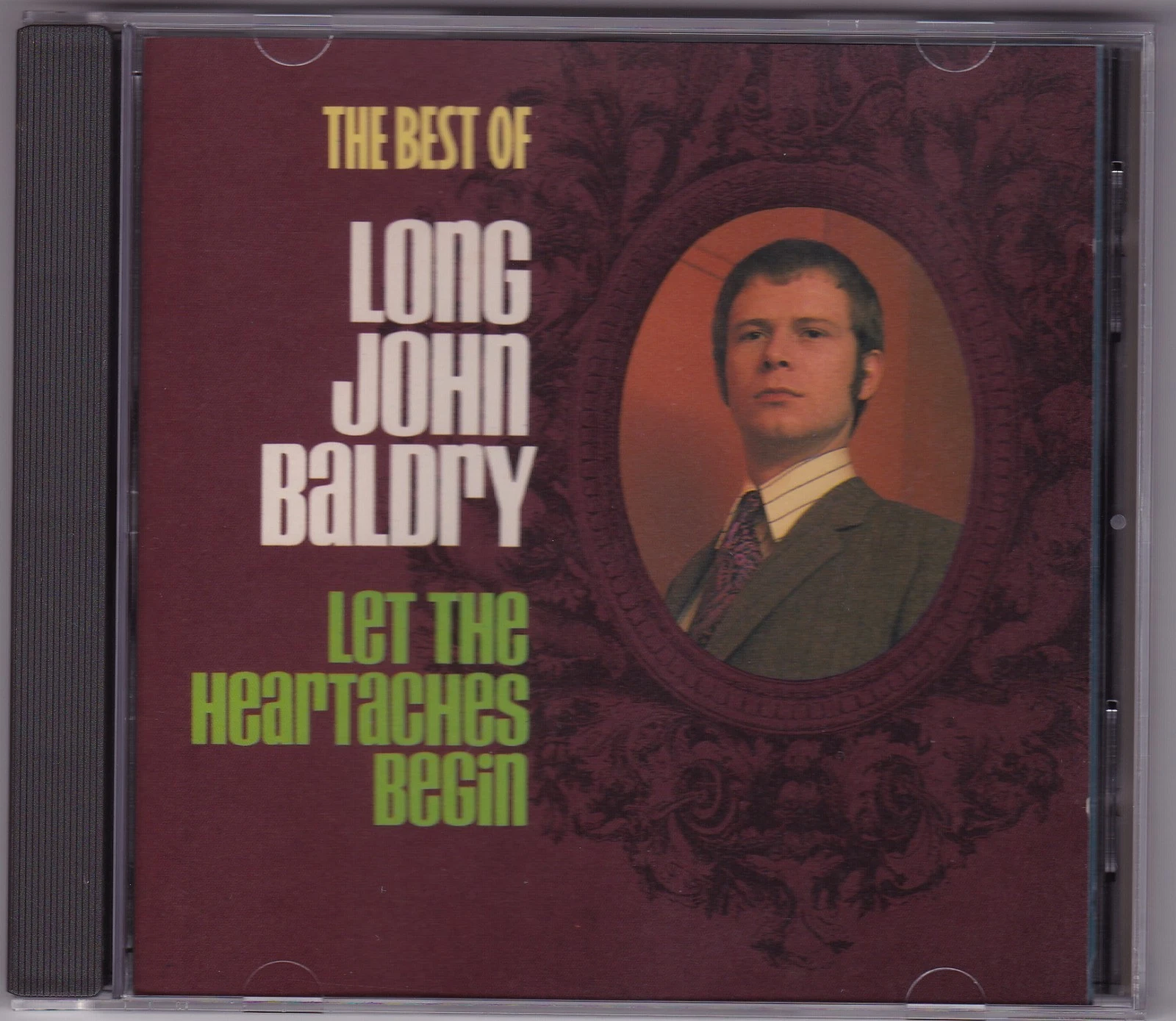

By the mid‑1960s, Baldry’s name carried serious weight in British blues circles, but the mainstream had only glimpsed him. That changed when he shifted toward a more polished, orchestrated pop sound, culminating in “Let The Heartaches Begin” in 1967. The song went to Number 1 in the UK, introducing that deep, resonant voice to a much wider audience. To blues purists, it sounded like a departure, but to Baldry it was another extension of his broad musical taste and his love of a great song, whatever the genre.

What’s important, though, is not to mistake that pop success for his whole story. The man who crooned a string‑laden ballad was the same one who had roared through Chicago blues tunes at the Marquee and taught a young Rod Stewart how to stand tall behind a microphone. Long John Baldry never entirely abandoned the blues; he simply folded it into an ever‑widening palette that took in cabaret, easy‑listening, and later, more introspective singer‑songwriter material.

As trends shifted again in the 1970s, Baldry adapted once more. He recorded albums that leaned into rootsy, acoustic blues as well as more mainstream singer‑songwriter fare. He toured constantly, working both the club circuits and theatre shows, particularly embracing the cabaret and supper‑club environments where his storytelling, warmth and impeccable phrasing could shine. Onstage, he was a raconteur, mixing songs with anecdotes about the early days of British blues and the “kids” he’d once taken under his wing.

This cabaret period is sometimes written off as a sideline, but it reveals another facet of his talent: the ability to connect intimately with audiences. In smaller rooms, stripped of the raw volume of a blues band, Long John Baldry could rely on timing, charm and vocal nuance. The same skills that helped him nurture younger musicians—empathy, attentiveness, a knack for reading the room—also made him a compelling solo performer, even when the spotlight was softer and the arrangements more genteel.

Throughout all these shifts, one constant was his eye for talent and his generosity in sharing the stage. Musicians who played with Baldry often later spoke of him as both a boss and a benevolent mentor. He was the one who would tell a nervous new guitarist, “Take the solo,” then stand back and let them grow into the moment. He created spaces where untested players could make mistakes, learn fast, and develop the confidence that would carry them into bigger bands and bigger stages.

If you trace the family tree of British blues and rock, Long John Baldry appears again and again at crucial junctions. He was there as a foundational voice with Alexis Korner, there shaping the Hoochie Kooche Men during the gritty club years, there guiding SteamPacket’s high‑energy revue, and there giving both Rod Stewart and Elton John the tools—and in Elton’s case, even the name—to move from underground promise to worldwide fame. His personal discography is only part of his legacy; the careers he enabled are the other, equally important part.

In the broader story of the U.K. music scene, Baldry’s role is a bridge between eras. He connects the skiffle and trad‑jazz generation to the rock superstars of the 1970s and beyond. He also connects the smoky, low‑paid residencies of the early blues clubs to the slick, international cabaret circuits that many British performers eventually embraced. Following Long John Baldry’s career, you see how British music moved from subculture to mainstream, and how the people who lived through those changes adapted—or didn’t.

It’s also important to recognize that his contribution wasn’t just musical; it was personal. Baldry was known for his kindness and for supporting younger colleagues through private struggles as well as professional uncertainties. For artists like Elton John, that support was life‑changing. In an era when the pressures of sudden fame, personal identity and industry expectations could be overwhelming, having a steady, experienced figure like Baldry in your corner made all the difference.

For modern fans digging into the history of British blues, putting Long John Baldry back at the centre of the story changes the picture. Instead of a scene that magically produced stars, you see a network of clubs, bands and mentors. Baldry stands out as one of the key connectors: a towering front man with a resonant voice, a curator of the blues, a builder of bands, and a quiet architect of two of the biggest careers in popular music. His own records are worth revisiting, but so is his role as a catalyst.

Long John Baldry's Best Of album.

Long John Baldry's Best Of album.So when you hear “Let The Heartaches Begin” on an oldies station, remember that behind that one pop hit stands a much bigger legacy. Long John Baldry helped set the stage for the British blues explosion, shaped the early paths of Rod Stewart and Elton John, and showed, year after year, how to turn raw, nervous talent into confident, seasoned performers. That combination of artistry, mentorship and sheer adaptability is why Long John Baldry deserves a secure, permanent place in U.K. music history.

Enjoy this site? Share with friends!